Chapter 1

What happens inside a young person when they decide to run away from home? I remember my own first night on the run at around twelve. It felt alien, being up so late, but I’d been well prepared, with my clothes neatly placed under the mattress and a bag packed, ready to go. Trying to stay quiet, every noise amplified in my head as I filled

my school bag with such a foreign cargo and crept towards the front door.

There was no way I could close it; the noise would wake the whole tenement. So I snibbed it open, feeling a flicker of guilt, pulled it too behind me, and slipped down the five floors of the blackened- sandstone stairwell towards the final obstacle, the clattering, half-hinged downstairs entrance door.

What was I feeling? What was I thinking? I was a little scared, but mostly relieved. Relieved to escape the stifling discipline and painful beatings that had plagued my life and closed in my future. Relieved to have an open road almost before me, to embrace an adventure, and to

hope that somehow this road to nowhere might lead to something more.

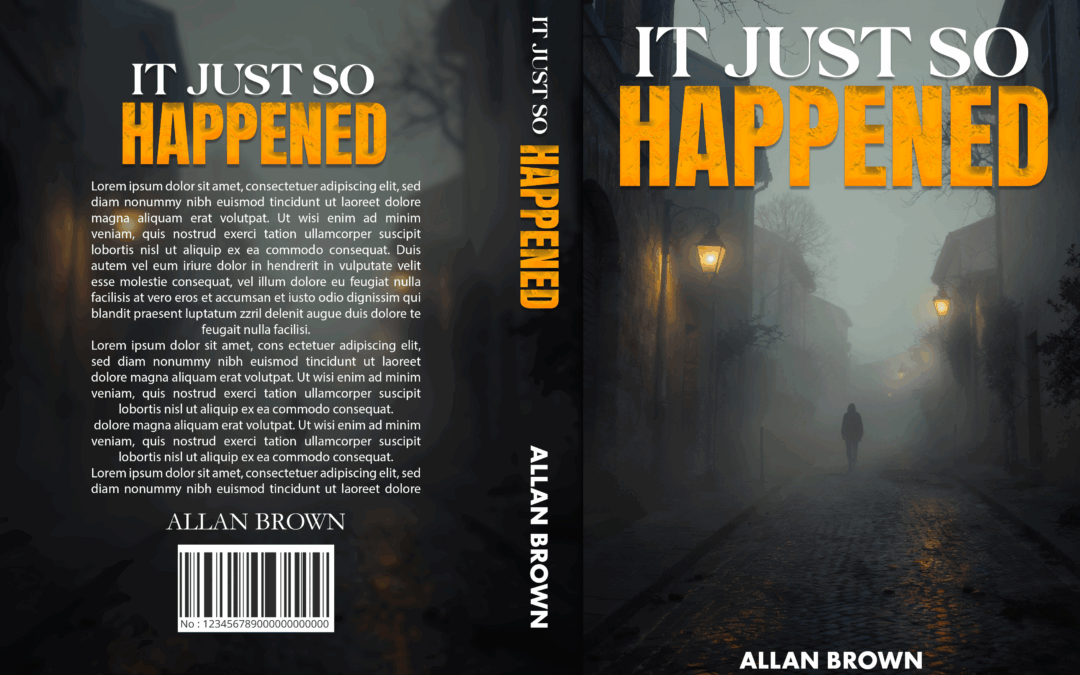

Slowly, like paint drying, I eased the stairwell door open, straining to take its weight and soften the creaks. Then I was out in the street, the sulphur-yellow streetlights casting a strange, quiet glow, shadows of hidden danger lingering at the fringes. The memories of endless tears

faded a little; a sense of purpose and hope gripped my young heart as I stepped out, tight against those shadowy edges, heading towards freedom.

I remember it as if it were yesterday, squinting at the oncoming car headlights reflected in the rain-washed, chilly Edinburgh streets. The sour smell of brewed hops drifted nearby in fleeting wafts. Heading to Portobello on foot, bag slung over my shoulder, I kept up a decent pace

to fight the cold. Yet it felt as though the whole world had opened to me, that nothing was impossible, and opportunity would come knocking if I could just stick it out. I think I was sensing the call of the open road, taking risks, travelling light. Something new was forming

in my green-stick-fractured character: a rising hope that change couldbe mine, waiting somewhere just ahead.

Memories of Enid Blyton’s Famous Five blended with Horatio Hornblower, The Jungle Book, and the echoes of Zane Grey urging me on from Riders of the Purple Sage. Oblivious to risk, I walked for hours. I did have a plan, if I could reach the outskirts of the city, I could put my thumb out, and I had faith someone would help me make some

distance.

My mind was fixed, and distance felt like the natural, straightforward goal. The real task was covering that initial stretch before daylight broke. Was I missing my warm bed, thinking of breakfast, or picturing

my family waking up? To my embarrassment, none of that crossed my mind. I was an adventurer, willing to travel as far as needed and endure whatever hardships came rather than return to an emotional prison,

where sterile enamelled gates waited with silent anger, dour, violent, and vindictive.

As I walked along the mostly empty streets, I kept clear of the busier main roads and did my best to avoid any lone pedestrians. Self-conscious and aware of my own strangeness, I slipped briefly into the far-off shadows at the edge of the pavement, away from the random

sweep of prowling car lights. As I walked, my mind drifted back to a past event. There were no soft-focus effects or harp music, only the sound of my own breathing and the irregular pulse of distant, sporadic traffic.

I was about four years old, sitting on the sink’s draining board, feet in the basin as my dad washed me. He asked me a strange question: “Is it sore?” I’m fairly certain I didn’t understand what he meant, but my eyes followed his gaze down to my own legs and buttocks. As I

stretched to look, I remember feeling a kind of amazement at the many shades mottled across my lower back and down to the backs of my knees, greens, blues, purples and even pinks. The colours carried a

worrying depth, yet strangely, there was no real pain.

“No,” I answered simply, although uncertainty echoed in my voice. “Hmm,” he replied, pausing before saying, “I think I’ll use something harder in future then, maybe a shoe or a cane.”

Said with such a straight face and calm manner that, at my young age (and even now), a wave of uncertainty passed through me, settling in with a shudder. I remember so clearly that I simply didn’t know what

to say.

All-night garage lights glinted in the distance, a sign of normal life, open and welcoming. A car sped past with its indicator already on, leaning toward the kerb as though it wasn’t sure it would make the turn. Normal life. How do I explain the disappointment that lived in my chest? The longing? The wonder at friends whose mums and dads

laughed, had messy homes and open doors. I wanted to steal a bit of their family joy and hide it under my jersey, holding it close in memory if I couldn’t have it in reality.

Soon I reached the petrol station, watching cars, and lives, go about their carefree business. Doubt settled into my mind and heart. Where was I going? I hung back at the edge of the forecourt, watching, thinking, waiting, uncertain. I sensed, more than understood, that I was

at a defining moment. Leaving the house had been easier than moving on now. Some sort of reluctance was rising; something final waited beyond the pumps, somewhere across the far pavement. A decision

would be made there.

Hesitation reached out as if to shake my hand. It wasn’t quite a stalemate, more of an impasse. A conversation churned in my head, but the words were thick and slow, making no sense. A hint of anxiety crept in; it wouldn’t take much to push me into panic.

For the first time, I felt the weight of my bag. I’m not sure how long I stood there, shuffling back and forth. Hesitation had invited indecision in, and they were settling comfortably.

A van pulled up at the nearest pump and a man stepped out to fill the tank. He looked up and smiled at me. I stared back with a faint smile, not wanting to be rude, but unfamiliar with the whole situation. When he finished with the pump and locked the petrol cap, he looked my way again and beckoned me over. “Hi son, cumoan over here,” I heard.

Head down, eyes fixed on my feet, I walked towards him.

“Whear ur ye goin’?” he asked.

In that split second, I decided I was going back. I gave him the name of a street near my home. I think I already knew he would offer me a lift before the words even left his mouth. He went inside to pay and made me come with him. I still wonder if he saw through the half-formed story I told him, even I can’t remember what it was, and simply wanted to help me get home.

Amazingly, though I had walked for hours, it took only a short time

before we reached the street. He asked for the exact house number, but

I dodged the question and jumped out with a quiet, “Thank-ye, mister.”

I headed down the street, nervous. Maybe my parents had woken in

the night, seen the open door, and the whole game was already up.

Rushing without running, I pressed on towards the stairwell. With a

little less concern for noise now, people were up and about anyway, I

climbed to the door. Still open. House still in darkness.

Silently, I worked the snib back into place once I’d closed the door,

then slipped into my room and, like a mime artist, put everything back

exactly where it belonged before climbing into bed. I knew I had about

ten minutes before the 5.30 alarm would ring and I’d be ordered to get

up.

It felt like a defeat in some ways, but my heart was singing. Something

new had opened up inside me, a possibility. I’d discovered a potential

escape route, and although I hadn’t used it fully, it now existed in my

mind. I had no idea, of course, that future journeys would last much

longer and take me hundreds of miles. But I sensed there were

adventures ahead, experiences that would reshape my world..

I enjoyed this first chapter, I’m curious about how Allan’s story unfolds. I’m looking forward to reading the rest of the book.